Context and policy overview

After Slovenia joined the European Union (EU) in 2004, it instituted separate nationwide collection and mechanical biological treatment plants for processing waste. These measures fell short of what was needed to process the country’s increasing amount of waste, however. The amount of waste produced by Slovenian cities increased by 55 per cent between 2002 and 2008.[1] In 2008, household waste accounted for 13 per cent of the country’s waste, but only 15 per cent of it was recycled; the rest went to landfill.[2]

As the country’s landfills started to reach saturation point, the Slovenian government changed national regulations on the types of waste that could be put in landfill and closed about half of all landfill sites nationwide. Cities were, therefore, in dire need of solutions to dispose of the growing amount of waste. In 2005-06, Ljubljana failed in two attempts to meet the challenge: (i) the construction of an incineration plant was brought to a halt by local objections and (ii) door-to-door biodegradable waste collection proved unpopular due to a lack of public knowledge of the benefits of waste separation.

Learning from these experiences, from 2011, Snaga Ljubljana, a 100 per cent publicly held company that managed municipal waste, set out to promote waste separation and collection and to minimise the amount of solid waste. By incorporating smart solutions into the existing waste management system, the company (i) monitored the amount of waste that citizens were producing and charged accordingly and (ii) optimised its waste-collection route based on population density and the size of neighbourhoods. By 2016, more than 63 per cent of collected waste was sorted correctly,[3] catapulting Ljubljana into the top echelons of European cities when it came to waste management. As part of its commitment to zero waste, the city aims to halve its amount of residual waste and to improve its recycling rate to 78 per cent by 2025.

Implementation

Phase 1: Rollout of waste separation and collection (2002-08)

The municipality of Ljubljana adopted waste sorting prior to the 2004 national policy. From 2002, Snaga Ljubljana had been installing colour-coded bins on sidewalks and asking people to dispose of recyclable and residual waste accordingly. Door-to-door collections of biodegradable waste started in 2006, as this accounted for the bulk of household waste. However, neither approach led to more effective waste collection. No campaign had been launched to raise public awareness of the value of waste sorting, resulting in the low usage of both collection services.

Phase 2: Overhauling waste collection services (2011-13)

Drawing on lessons learned, Snaga Ljubljana embarked on changing people’s attitudes towards waste separation and collection. It overhauled its payment system and reinvented the way waste was collected. Before implementing its plan in Ljubljana, the company launched a pilot project in Brezovica, a small city adjacent to Ljubljana, by:

- reducing the volume of residual waste containers on the roadside

- collecting bins for paper waste and packaging less often

- imposing variable tariffs on different types of household waste.

This pilot project was highly successful, with the amount of recycled packaging increasing threefold and residual waste dropping nearly 30 per cent.[4]

Snaga Ljubljana then introduced a number of changes to the city’s waste collection services in 2012: (1) a pay-as-you-throw system, (2) upgraded door-to-door collections and (3) a campaign to raise public awareness of waste separation and collection.

- Pay-as-you-throw system

To maximise use of the city’s public areas, Snaga Ljubljana started moving city-centre kerbside waste containers underground in 2012 (Figure 1). Recyclable, bio and residual waste was redirected to underground public bins; those for recyclable waste were accessible to all, while biodegradable and residual waste bins could only be opened with a smart card, which all residents received free of charge. People used the cards to record the amount of waste they threw and were charged accordingly at the end of the month.

Figure 1. Underground public bins in Ljubljana

Source: Ljubljana: Zeroing in on waste 2015[5]

To streamline the payment system, two sizes of bag were designated for underground bin use: a 30-litre bag for residual waste and a 10-litre bag for biodegradable waste.[6] This allowed the smart card to record the number of bags put in the waste, rather than weigh each one. Fifty-six underground public bin sites had been installed as of the end of 2016 and the number continued to grow, with the aim of ensuring that every resident had access to underground bins within 150 metres of their home.[7]

- Upgraded door-to-door collections

In 2013, Snaga Ljubljana introduced a door-to-door collection for recyclable materials and residual waste in addition to biodegradable waste, which was sorted into three colour-coded bins owned by each household. Two improvements were made to the existing door-to-door collection to promote waste separation collection:

- Optimised waste-collection frequency: The frequency of waste collection was optimised based on the population density of neighbourhoods. In less populated neighbourhoods, the residual waste collection was reduced from weekly to once every three weeks. In heavily populated areas, collections were conducted weekly. SMS messages were sent to remind residents of the collection schedule. In contrast to residual waste, biodegradable waste and recycled materials were still collected several times a week.

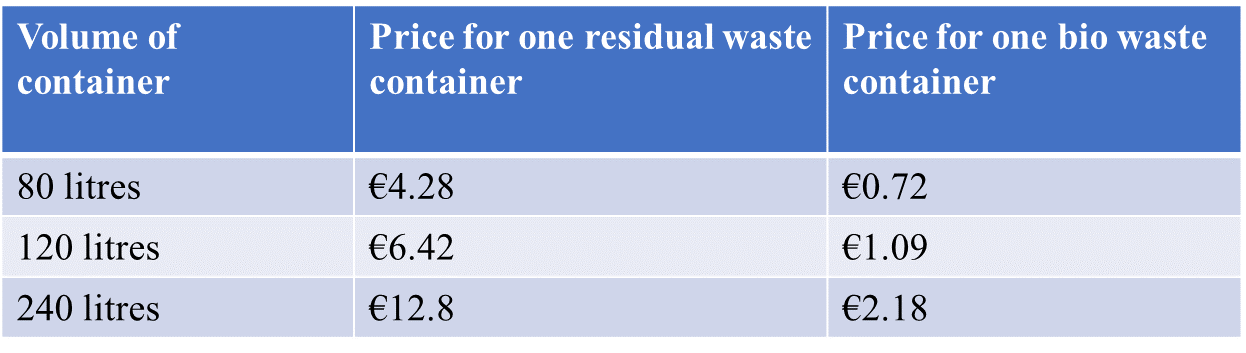

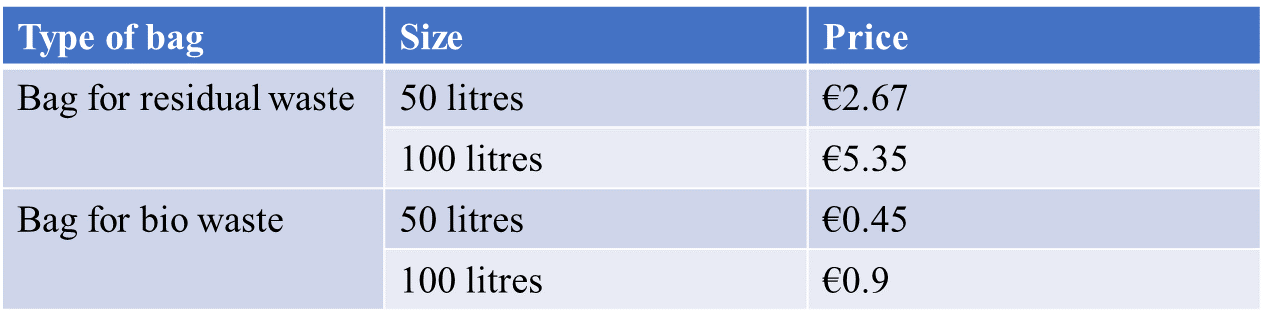

Variable tariffs: The city also imposed different tariffs for residual waste and bio waste. A container for residual waste was six times more expensive than one for compostable waste (Figure 2), for example. The same principle was applied to rubbish bags. The more residual waste produced, the higher the waste collection fee.

Figure 2. Residual and bio waste price comparison

Source: JP Vodovod Kanalizacija Snaga, 2020[8]

Although locals opposed both policies initially, the city pressed ahead with its plan to promote waste sorting. Snaga Ljubljana invited national and local media to visit the city’s landfill site to quell local objections. Media outlets joined efforts with the company to persuade residents to separate their rubbish more efficiently after seeing the number of recyclable materials mistaken as residual waste.

The new payment system also helped to promote waste separation. Citizens were motivated to produce less residual waste, as it cost more than recycling and composting, which reduced household waste collection fees. The average cost of waste management per household in the city fell to €100 a year, well below the national average of €150 a year.[9]

- Greater public awareness of waste separation and collection

Educating the public on how to sort rubbish correctly was a priority for the city, which used multiple tools to communicate the message:

- The correct waste-bin combination was posted on Snaga Ljubljana’s web page, on an app and on the back of households’ monthly invoice.

- Programmes were designed for children of different ages to teach them the value of waste sorting.

Phase 3: Promoting zero waste[10] (2014 to present)

Ljubljana started to shift its focus from reducing waste to achieving zero waste in 2014. Snaga Ljubljana, therefore, opened two new collection centres where residents could bring second-hand items. Damaged items were repaired and given a new chance of life. There was also a mobile unit for recycling electronic devices and hazardous waste. Residents could recycle their devices at no extra cost. Over the course of 2014, about 130 tonnes of hazardous waste were collected from households.[11]

In 2015, at the city government’s behest, Snaga Ljubljana transformed a landfill site into a waste-treatment centre, called RCERO Ljubljana. The project cost €155 million and was jointly funded by the European Union (EU) Cohesion Fund, the Ljubljana city government and the Slovenian national government.[12]

The centre processes two types of waste: (i) biowaste and (ii) residual municipal waste. Biowaste undergoes an anaerobic fermentation process to produce gas, which is then used to power the centre. The centre is able to process more than 200,000 tonnes of biowaste annually.[13] Residual waste is sent to a mechanical treatment facility, where recyclable materials are extracted and solid fuel is produced. Following the process, only 4.9 per cent of residual waste ends up in the city’s landfill.[14]

Barriers and critical success factors

Ljubljana’s initiative to reduce municipal waste got off to a slow start because of the public’s passive response. There were neither incentives nor campaigns to communicate the value of waste sorting to residents, resulting in low recycling rates in the first few years.

To resolve the situation, Snaga Ljubljana worked with the media on awareness campaigns and redesigned its payment system for waste collection, making recycling and sorting rubbish more financially rewarding for residents. This strategy gradually changed citizens’ attitude towards waste sorting, making Ljubljana one of the leading European cities in terms of recycling rates.

Good policy coordination also contributed to the city’s success in waste management. Technology played a vital role in the new waste collection services, but other measures were equally important. For instance, before issuing smart cards for the underground bins, Snaga Ljubljana designed specific bags. It standardised the sizes used to calculate the amount of household waste produced, then charged accordingly. It is worth noting that technology is not a one-size-fits-all solution; cities must put things into context for residents and create a holistic policy.

Results and lessons learned

The optimisation of door-to-door collection frequency improved Snaga Ljubljana’s operational efficiency. It reduced the time needed to collect the same amount of waste by 10 per cent and shortened collection routes by 17 per cent.[15] This gave the company scope to lower waste-management costs per household from €10 to €7.96 per month,[16] prompting residents to recycle their waste more efficiently.

Ljubljana saw an increase of more than 10 per cent in the recycling rate from 2013 to 2018. Around 55 per cent of waste was sorted at source as of the end of 2013, rising to 68 per cent as of end 2018.[17] Not only did the city dump nearly 80 per cent less rubbish in landfill, but it also wasted less. In 2014, Ljubljana generated just 157 kg of waste per capita,[18] in marked contrast to the European average 475 kg. Thanks to its environmental record, Ljubljana was named European Green Capital in 2016.

Cities interested in reducing their solid waste and promoting a greener society can learn from Ljubljana’s experience:

- Awareness campaigns to educate the public on the value of recycling contribute to successful waste sorting. Effective communication helps to reduce the risks of local protests against new policies that might inconvenience citizens in their daily lives.

- Cities should consider adopting a two-pronged approach to encouraging citizens to recycle. In addition to raising public awareness of recycling, a well-designed payment system that rewards recycling and composting is also important.

- Incorporating ICT tools into the city’s existing waste collection services is a key enabler, but it is not the sole success factor. Cities need to adopt a comprehensive policy that tackles different problems in waste management.

Ljubljana city started its waste separation two years earlier than required by the national government. The success of the country’s capital city encourages other cities to follow suit.