What are Nature-based Solutions?

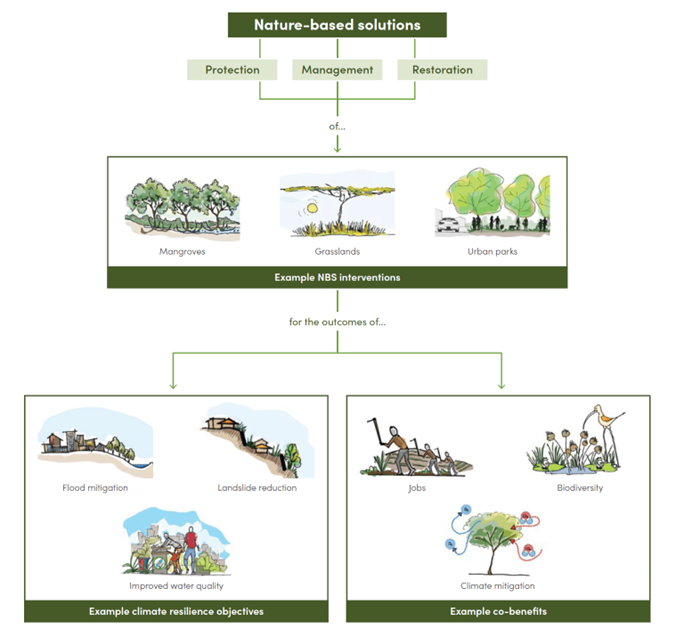

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), defines nature based solutions NbS as “actions to protect, sustainably manage and restore natural and modified ecosystems in ways to address societal challenges effectively and adaptively, to provide both human well-being and biodiversity benefits”. IUCN pioneered the concept of NbS 20 years ago, first formulating a formal definition then developing rigorous standards to inform the design, implementation and evaluation of interventions. NbS may involve protecting, managing or enhancing existing natural solutions and creating engineering solutions that mimic processes. Common NbS include constructed wetlands, mangrove restoration, green roofs and walls.

Why do we need NbS?

The sustainable development of natural capita, which encompasses the Earth’s natural resources such as geology, soil, air, water and all living organisms, plays a crucial role in achieving the UN SDGs. For years, organizations such as the IUCN have implemented conservation initiatives that not only protect, manage, and restore the environment, but also provide lasting benefits for the people around them. This approach, known as NbS, is increasingly recognized as essential for integrating nature conservation into key economic sectors. Many experts agree that NbS are a critical tool for tackling the twin global crises of biodiversity loss and climate change.

Research suggests that the ecosystem services contribute over USD 125 trillion annually to the global economy. Climate change and biodiversity loss pose significant threats not only to nature but also to the global economy, as economic activity is deeply interconnected with the environment and cannot occur in isolation. (EIB, 2022) NbS therefore offer business opportunities to reduce costs, generate revenue, and enhance environmental outcomes.

High-quality NbS projects could mitigate up to 10 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide (GtCO2) per year, equivalent to around 27 per cent of current global emissions. In other words, NbS could provide around 30 per cent of the cost-effective mitigation needed by 2030 to stabilise warming to below 2 degrees Celsius (UNEP, 2022) Additionally, data from 194 empirical studies have proven that the use of NbS for climate change adaptations has been effective at reducing climate impact. Among the six most reported climate impacts being addressed by NbS there were water shortages, soil erosion, timber loss, flooding, biomass decline and food production loss.

The Financing Gap: Challenges and Opportunities

While biodiversity loss and ecosystem collapse have been rated by the World Economic Forum as one of the top 5 risks over the next 10 years, the financing gap to address these issues is estimated at USD 700 billion per year. According to the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), only 17 per cent of total investments in NbS are currently from private finance. UNEP’s State of Finance for Nature report shows that finance flows to NbS are currently USD 154 billion per year, less than half of the USD 384 billion per year investment in NbS needed by 2025 and only a third of investment needed by 203

At the samtime, buy rapidly doubling financial flows to NbS, we have the potential to halt biodiversity loss, reduce emissions by 5 GtCO2 /year by 2025 further rising to 15 GtCO2 /year by 2050 in the 1.5°C scenario and restore close to 1 billion ha. of degraded land.

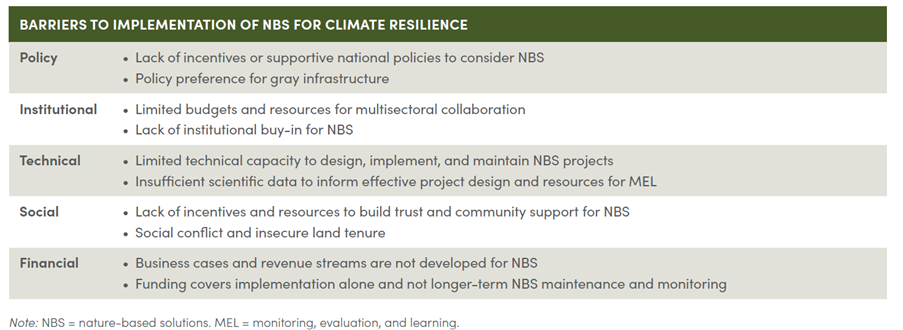

NbS represent an exciting emerging area of finance with many opportunities for financial institutions, but many challenges remain in financing and implementing effective NbS. The key barriers to investment in NbS include: (i) limited availability or quality of information on returns and impact; (ii) insufficient capacity within the financial sector, such as lack of expertise to assess risks, inadequate training, and unfamiliarity with innovative financial products; and (iii) a shortage of investable projects, characterized by low volumes, small-scale deals, and poor bankability of existing opportunities. Additionality, the complexity of natural systems leads to greater uncertainty in returns, making it less appealing to risk-adverse investors. Other challenges stem from the nascent and small-scale nature of the NbS asset class, which leads to high transaction and structuring costs. There is also a growing risk of greenwashing, where activities are labelled as NbS without adhering to IUCN guidelines, or without delivering clear environmental or social benefits. To address these issues, it is essential to establish clear, science-based standards that define best practices in the NbS space.

On the other hand, NbS can offer quantifiable benefits in economic returns and growth. For example, NbS can increase project revenues by identifying new revenue streams and pioneering new markets. Further, there are considerable opportunities to be gained by directing capital to NbS projects in terms of identifying and mitigating climate and nature-related risks in financial portfolios. The contribution to developing net zero and nature-positive strategies with NbS is significant due to their emission mitigation potential, highlighting their value in increasing financial institutions’ sustainability and climate action. Other mechanisms include improved product yields leading to increased revenue (e.g., higher agricultural yield through sustainable land management), higher mark-up of products or services with sustainability accreditation, increased resilience to market changes with strong natural systems, and lower future costs of operations through increased investment in NbS. However, it is evident that public finance is essential to drive the advancement of nature-based solutions and to offer guarantees that encourage private investments.

Scaling up NbS Implementation

Unlocking the full potential of NbS requires systemic change. Multilateral organizations, donors, and civil society must increase investment in early project preparation, technical capacity, and monitoring. To scale financing, the public and private sector must expand innovative tools like green bonds, dedicated national funds and risk sharing mechanisms.

The “Growing Resilience: Unlocking the Potential of Nature-Based Solutions for Climate Resilience in Sub-Saharan Africa” report from the World Resource Institute and the World Bank analysed nearly 300 NbS projects in SSA – one of the most vulnerable regions to climate change in the world. from over the past decade. The report reveals positive trends and significant momentum in NbS projects initiating and funding, however as more is needed, the report provides a set of strategic recommendation to scale up NbS implementation:

- Better Integrated NbS into relevant policies and plans to institutionalize their role in addressing climate and development challenges. This includes incentivizing NbS by plans and policies for urban development and update policy and regulatory frameworks to remove barriers and unlock funding for NbS.

- Improve NbS project preparation and NbS-specific technical capacity to develop a project pipeline. This includes disseminate lessons and best practices through peer-to-peer learning, practitioner forums, and knowledge exchanges to increase early-stage project preparation by project developers.

- Diversify funders and funding sources by applying a mix of conventional and innovative financial mechanisms.

- Improve monitoring, evaluation, and learning to ensure projects deliver intended climate impacts and co-benefit.

- Enhance NbS project integrity and effectiveness by incorporating gender equity and traditional knowledge, increasing responsiveness to community needs, and safeguarding biodiversity.

Urban implementation of NbS: the case of Augustenborg, Malmo

Urban areas account for 70 per cent of global CO2 emission, and with over half of the world’s population living in cities, urban areas contribute significantly to climate change and the loss of diversity. However, if planned well, cities also represent unique opportunities to reduce humanity’s environmental impact. And municipal administration and city planners play a key role in pioneering and financing the implementation of urban Nbs.

One early example of Urban NBS was in the Augustenborg area of Malmo, an area of built in the 1950 with several issues such as low incomes and criminality, but also flooding. In the late 1990s, the city responded with an ambitious programme to make the 32ha Augustenborg neighbourhood a more socially, economically, and environmentally sustainable place to live. This was made possible through a focus one energy efficiency, a botanical roof garden, , pollination preservation, rainwater collection and bioretention basins through open storm water management; all which relied on a committed community. The project was also successful thanks to its significant financial support, both from the EU and private funds. T

Two decades later, the project created 11,000 m2 of green roofs and 50 per cent increase in green spaces which increased the biodiversity. The neighbourhood today generates around 20 per cent less carbon emissions and waste, the risk of flooding has tangibly decrease with around 90 per cent of storm water led into the open stormwater system. Furthermore, the neighbourhood has also seen a decrease in the unemployment rate an increase in the elections participations. The success of this project has resulted in similar approaches across Malmö and many other cities in Sweden and beyond.

The first EBRD NbS: Chisinau River Rehabilitation

As part of plans to revive the Moldovan capital, Chisinau, formulated since the city joined the EBRD Green Cities urban sustainability program and approved its Green City Action Plan to address its challenges, the EBRD, co-financed by the European Investment Bank and the Green Climate Fund, financed a project to regenerate the river Bic and transform it into an attractive asset for its residents and the region. The Chisinau River Bic Rehabilitation and Flood Protection project is the EBRD’s first project to formally implement a form of NbS.

As Chisinau has grown, the river Bic has become polluted and is prone to flooding, impacting local communities, infrastructure, and the economy, reducing the appeal of the city. Severe flooding is expected to become more harmful with the predicted impacts of climate change, which is likely to bring more short, intense downpours.

The project, still in its early stages, will finance the partial rehabilitation of 7.6km of the city’s river, including cleaning and a set of integrated floodwater management measures, such as rehabilitating the drainage network and installing flap valves along the urban reaches of the river to mitigate the increased risk of severe flooding events due to climate change. More broadly, the project will restore water quality and the river’s appeal.

In addition, the project plans to retrofit approximately 90 rain gardens and 85 tree pits in urban settings, examples of sustainable urban drainage solutions (SUDs) that use engineered natural systems to manage surface water runoff and enhance its water quality. These will also create green spaces that complement more traditional stormwater management systems.