Context and policy overview

Curitiba, in southern Brazil, is considered one of the world’s most successful examples of how to plan, build and operate a municipal bus rapid transit (BRT) system. In the 1970s, the city introduced the BRT system to ease congestion on its roads. Between 1990 and 2000, the city government subsidised travel and installed an e-ticketing system to encourage the public to use it. Despite its popularity, however, in the new millennium, the bus transport system faced fresh challenges in the face of economic and population growth. An increasing number of people were opting for private vehicles over the BRT system and ridership decreased 4.3 per cent between 2008 and 2012.[1] Studies suggested a lack of punctuality and a last-mile solution as possible causes for the decline in popularity.[2] Consequently, the Urban Development Authority of Curitiba (URBS) decided to overhaul the BRT system, implementing a series of improvements.

The URBS adopted a two-pronged approach to modernising the BRT system. First, it built a new BRT corridor connecting the major terminals and outlying suburbs to accommodate passengers with limited access to public transport. Second, the city partnered with private enterprise to create an intelligent transport system, including measures such as dynamic traffic management, traffic priority signalling and real-time bus information. The government further embarked on improvements in the city’s cycling infrastructure, adding bike lanes and racks in neighbourhoods adjacent to BRT corridors.

Implementation

Curitiba’s BRT system was originally built in 1974.[3] In tandem with its development, the city government adopted strategic approaches to meet the challenges that arose at different stages.

Phase 1: Incentivising ridership

The URBS and bus operators upgraded the city’s BRT system incrementally to match municipal growth in a sustainable way. The prefecture of Curitiba was the largest URBS shareholder – a municipal company with the power to steer the development of the public transport system.[4] In the first two decades of project implementation, the Curitiba government aimed to build an integrated transit network to guide the city’s land-use policies. It constructed an east-west arterial corridor dedicated to bus transit and introduced a flat fare to facilitate transfer between different modes of public transport.[5]

At the time, two factors impeded passengers from taking buses. An old-school payment method resulted in delays as passengers formed long queues to buy tickets from drivers, with a knock-on effect on bus departure times. Moreover, the bus fare was not affordable for low-income groups. To tackle these challenges, the city government launched an electronic ticketing system to speed up payment and offered incentives to low-income people to promote the use of the BRT system.

In 2002, an electronic ticketing system replaced conventional coin-based payment to accelerate boarding and curtail fare evasion. While express and direct buses required passengers to prepay at stations and terminals, other types of buses allowed passengers to pay with a contactless transport card on embarking. According to the URBS, around 60 per cent of passengers opted for contactless payment when e-tickets were introduced.[6] The elderly and people with disabilities were issued with transport cards that entitled them to lower bus fares.[7]

The e-ticketing system was developed and installed together with Vivo, Brazil’s leading mobile operator, Dataprom, a Brazilian supplier of public transport solutions, and Swedish telecoms giant Ericsson.[8]

In addition to Curitiba’s e-ticketing system, the city has launched various incentive programmes. In 2005, the city government cut the Sunday bus fare by 50 per cent to encourage ridership.[9] In addition, multiple groups, including the elderly, children below the age of five, students and people with reduced mobility, travelled free on any BRT service. A unique programme the city undertook to improve social inclusion and the use of public transport was “Garbage that’s not garbage.” The programme encouraged people to sort their residual waste and bring recyclables to waste stations in exchange for bus tickets.[10] This meant that residents of impoverished areas could travel to the city centre by affordable means and access more employment opportunities.

Phase 2: Technical transformation

Since 2009, the City of Curitiba has implemented significant changes to the operation and management of the BRT system. The goal was to improve the user experience and to provide greener public transport. Measures included: (1) the operation of a Green Line and (2) the introduction of an intelligent transport system.

The Green Line was Curitiba’s first step in improving the BRT system’s operational efficiency. The city’s first corridor incorporated segregated bus lanes, allowing different types of BRT services to operate simultaneously without encroaching on each other’s schedules.[11] Stations built along the Green Line provided sufficient space to accommodate local, direct and express services, creating an extensive transport network that connected more neighbourhoods than ever before.

Green Line in Curitiba, Brazil.

The Green Line also demonstrated the Curitiba government’s ambition to increase the sustainability of public transport. It was one of the world’s first bus systems to operate using 100 per cent biodiesel. In summer, the stations used rainwater to cool their interior temperature. The Green Line was estimated to emit 30 per cent less carbon dioxide and 70 per cent less smoke than buses fuelled by diesel.[12]

The city also implemented measures to improve the operation and management of the BRT system through an intelligent transport system. In 2013, the City of Curitiba established a public-private partnership (PPP) with a consortium comprising Indra (a Spanish company), Esteio and Dataprom (two local enterprises specialising in integrated monitoring systems) to develop an intelligent transport system.[13] The lead company, Indra, had had a long working relationship with the Brazilian government, implementing its terrestrial infrastructure modernisation project throughout the country. Two years prior to the PPP, the Curitiba government had worked with Indra and Esteio to pilot a traffic-light control system and test priority bus signalling in two affluent areas.[14] Based on the success of these pilots, the city awarded the consortium a US$ 15 million contract to develop more efficient and environmentally friendly public transport.[15]

The resulting intelligent transport system comprised (a) dynamic traffic management, (b) a priority signalling system and (c) real-time bus information. The goal of the system was to streamline urban traffic management and enhance the efficiency of citywide public transport.

- Dynamic traffic management

The intelligent transport system combined the URBS’s operations centre and other data sources, such as video detectors and a surveillance system, to develop a dynamic traffic plan that evolved with the traffic. The operations centre monitored the city’s fleet of 2,500 buses in real time through on-board computers, GPS modules and sensors,[16] which collected information including bus location, adherence to schedules and estimated travel time, sending it back to the operations centre each minute.[17]

The system also identified areas prone to congestion and proposed alternative routes using predictive algorithms.[18] Any route changes would be communicated to drivers through a message panel installed in the buses.[19] All data transmitted to the operations centre were stored as open data in its database for research purposes.[20]

2. Priority signalling system

The priority signalling system analysed the geolocation of every bus to optimise its travel time.[21] By linking the GPS module, or automatic vehicle location (AVL), in every bus to the operations centre, it was possible to adjust the timing of traffic lights when a bus was approaching and give it signal priority.[22] The system identified the appropriate intersections for such prioritisation, calculated the optimal travel time of each bus and adopted the best course of action based on the traffic conditions at the various intersections.[23] It also took into account factors such as the location of bus stations, the design of bus lanes (segregated or non-segregated lanes) and bus occupancy rates.[24] Based on this analysis, the operations centre could trigger green lights for buses as needed.

3. Real-time information

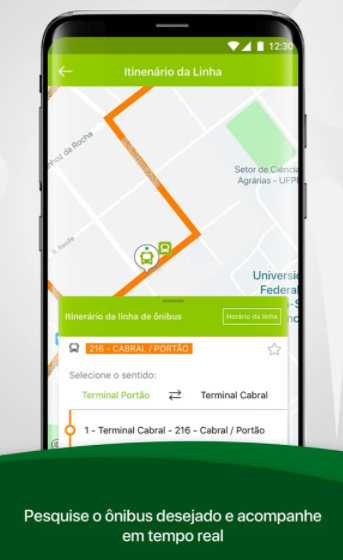

Leveraging the AVL, the operations centre published information such as changes in route, deviations and estimated travel times on a phone application named “Curitiba 156”. Furthermore, electronic panels were installed at stations that indicated bus arrivals and departures in real time.[25] On-board electronic panels provided the estimated travel time to each station, so passengers could anticipate the time it would take to travel to their destination.[26]

Curitiba 156.

Phase 3: Sustainable public transport

As the city’s population continued to grow, mobility remained a challenge, especially the issue of the “last mile”. Along with the technical transformation of the BRT system, the city government decided to promote cycling to build a more integrated and sustainable public transport system. In 2012, a bicycle-sharing system was implemented as a pilot project and will resume after the revision of an urban cycling route.[27] The city is estimated to be investing about US$ 40 million in creating a cyclist-friendly environment.[28] The first step consisted of renovating the existing cycling infrastructure and extending bikeways by another 200 km.[29] Bike lanes were constructed along BRT corridors and bike racks were installed at almost every station.

Barriers and critical success factors

Declining ridership was the major difficulty the BRT system encountered. Despite its initial popularity, ridership trended downwards in the 2000s due to unpleasant passenger experiences caused by delays and unpredictable timetables. To resolve this complex problem, the city government implemented gradual changes.

First, it set clear and achievable goals centred on improving the passenger experience and promoting environmental sustainability. Second, the city focused on small wins rather than being over-ambitious. Suitable technical solutions were found to different issues. The successful implementation of each stage laid the groundwork for the project’s ultimate success.

Lastly, the city involved citizens in improving system service quality. For example, it provided green incentives to low-income passengers to promote ridership, social inclusion and environmental protection.

Results and lessons learned

Since its launch in 1974, Curitiba’s BRT system has undergone a remarkable transformation, leading to better operations and management. To date, public transport accounts for nearly 50 per cent of all travel and commutes in the city, while private vehicles only account for about 26 per cent.[30] The rider experience has improved significantly; users rate all seven corridors “good” when it comes to service quality.[31]

Furthermore, the BRT system has successfully promoted environmental sustainability. Optimal operational efficiency combined with biofuel buses has resulted in a 50 per cent reduction in smoke and pollutants, as well as around a 35 per cent decrease in public transport fuel consumption.[32] These results have encouraged the city government to adopt more biofuel buses and increase their monthly mileage by 70 per cent.[33]

Curitiba’s success has inspired other cities around the world to follow its BRT lead. For instance, Bogotá, Colombia has adapted Curitiba’s BRT system to local needs with considerable success.[34]

Cities interested in developing or renovating their public transport systems can learn from Curitiba’s achievements:

- Cities should break down the issues they encounter into small components. In the case of Curitiba, the decline in ridership could be attributed to the problematic ticketing system, a lack of punctuality and a lack of incentive. The city government tackled each issue individually, rather than adopting a one-size-fits-all solution.

- Cutting bus fares is not the only way to enhance social inclusion. Curitiba’s Green Line incentive programme is a case in point. The city encouraged low-income families to recycle residual waste in exchange for bus tickets. The programme not only improved the city’s sanitation, but also provided affordable transport options for citizens living in poor outlying areas, linking them with more economic opportunities in city centres.

- Incremental progress eventually leads to success. When tackling a tricky problem, cities should adopt a comprehensive strategy, but implement gradual change. Focusing on the satisfactory completion of each stage of implementation paves the way for an overall win.

- It is important to design a mechanism that allows the traffic operations centre to control the traffic or intervene without causing traffic chaos.

- In addition to the aforementioned challenges, low ridership may stem from the lack of an integrated system. Providing solutions to the last-mile issue is essential to promoting public transport. In practice, a bicycle-sharing system is commonly used to resolve the problem.